We often overlook that cities are not just shaped by the municipalities, but also the people running through its sidewalks, the passengers riding on their cars and buses, the people living in the high and low buildings throughout the area. Their daily activities and how they go about them reflects the city itself, and often it’s through these everyday habits that the actual city is physically manifested.

Women, despite having been through a long line of history segregated away from the public sphere, have always had their own effects on the city. Despite having been chained in their own respective houses, women were still able to impact how most cities were developed and these impacts can still be felt to today’s society.

Notably, throughout history, there has been an active participation of Women of Colour (WOC) in creating the urban environments we see today. It’s more specifically seen through their works in communty involvement and activism that they create communities within neighbourhoods.

The Art of Home-Making

To better understand their role in city-making, it’s easiest to see women’s role in smaller scales and to compare how they’ve affected those spaces to their neighbourhoods and later on the city – the easiest being in their involvement in the process of home-making.

Bell hooks, a significant author in feminist literature, credits her mother and grandmother in the creation of the homes she grew up in, and highlights the importance of black women in the art of home-making, especially within the political environment of rampant racism when safe spaces for black communities were especially needed. In her essay titled Homeplace (A site of Resistance), she writes, “Historically, black women have resisted white supremacist domination by working to establish homeplace. It was more important that they took this conventional role and expanded it to include caring for one another, for children, for black men, in ways that elevated our spirits, that kept us from despair, that thought some of us to be revolutionaries able to struggle for freedom” (385).

From her story, it becomes clear that there’s an undeniable string connecting women and the art of creating the comfortable home. This is especially important to note within Black communities, as she writes about how it was these housewives who despite everything they had to face working for affluent white households had allotted the time and effort to create the home, a space free of oppression and for families to express discontent with the racism they had faced during their day.

And though it’s unclear whether hooks herself was aware of it or not, this theme of WOC placemaking their surroundings is a common thread found in many neighbourhoods of marginalised communities.

From the Home to the Neighbourhood

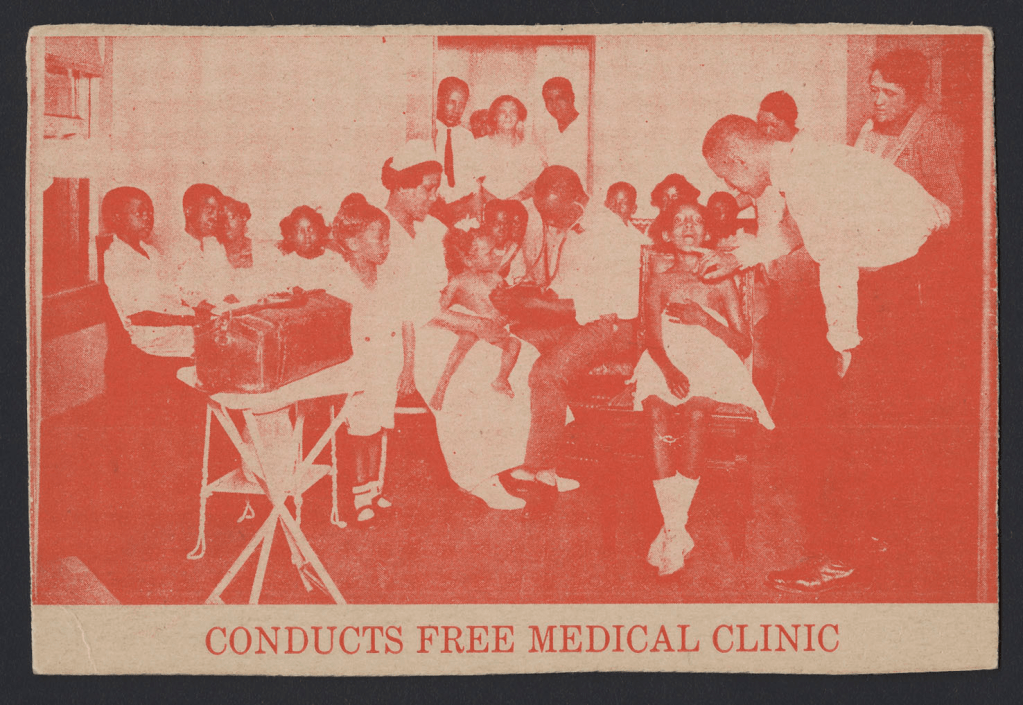

Outside of the home, black women have also played an active role in shaping the city through grassroot movements and active participation in civil activism. According to Elder et al., since the late 1800’s, black women have committed to creating activist clubs such as the “National Association of Colored Women (NACW), the Neighborhood Union[s],” and more, and that their efforts continued throughout the 20th century as a result of the exclusion of black women in feminist discussions and movements of that time. Members of such clubs like the NACW would hold conventions to discuss reformations needed to improve the social life and standings of black women, including “lynching, suffrage, childcare, elderly care, job readiness, fair wages, segregation, housing and women’s health” (NACWC). The Atlanta Neighborhood Union, on the other hand, focused on getting community members get the help they needed, including working closely with orphanages for black children, providing free kindergarten and daycare services to working mothers, and even held surveys to help assess neighbourhood needs (AUC Robert W. Woodruff Library).

But aside from movements done by black women, it’s the similar movements done by other women of racial minority which establishes the pattern this article aims to highlight.

Women of Calgary’s Chinatowns, for example, were often going out of their way to educate and care for their neighbourhoods in ways that the government had failed to do so, including providing food for unemployed members of their community, and were often running large community events such as their annual Chow Mein Teas. Though these women were small in number, it was the Mother’s Club that Lem Kwon had founded in collaboration with the Women’s Mission Circle that stepped up for their community and provided for the neighbourhood (Heritage Calgary).

More contemporarily, WOC continue their work in placemaking to spread comfort and community to their neighbours. For example, neighbourhood house events such as bingo nights, and free English-speaking lessons are provided by Latin-American women in Vancouver to offer an escape to their fellow community members, ease the process for first-time immigrants learning a foreign language for their first time, and establish a circle of support and friendship (Salamanca).

Though the circumstances that these women faced were bleak, there’s a certain beauty in these similar situations; a comfort knowing women all around the world were unknowingly doing the same thing that is banding together to create the neighbourhood spaces free of the oppression of their closed-minded surroundings.

Involvement in Today’s World

However, with the recent change of tides in women’s rights, it now begs the question, how quiet are our city-making processes now?

Feminism plays an undeniable role in the movement of women’s involvement, especially seen with the increased advocacy for gender equality.

With the rise in feminism, we see the concurrent uprise of feminist urbanism. Though it’s difficult to reduce feminist urbanism to one definition, it can generally be described as the work in erasing the leftover traces of patriarchy within our cities, and making the city that better protects and works for everyone. An example of such cities surfacing could be seen with the city of Aspern in Vienna; it aims to create the city with women in mind, from naming public spaces and streets after feminist thinkers, to offering accommodations for the needs of its women through its use of “gender-mainstreaming” by creating policies on the basis of protecting gender equality (Hunt).

Additionally, the urban planning field, especially one that we know now, had been influenced significantly with female thinkers throughout its years. From older thinkers such as that of Jane Jacobs and Hannah Arendt, to more contemporary contributors such as Amanda Burden – it’s undeniable that women have made a name for themselves within the industry.

However, as a 2024 article explains, there is still a notable lack of involvement from women of colour in the field. Though urban planners stand with a awfully close 50:50 ratio of male and female workers in the US, there is still an overrepresentation of white planners in the field, holding 75% of the jobs in the industry (Data USA, 2022). But this overrepresentation is not only felt through the demographics of urban and regional planners, but also in how planning still is carried out and affects our communities today.

Practices such as redlining that have historically been done to further segregate Black and Brown American communities may have officially been erased from our policies, but its effects are still felt today with higher chances of mortgages still being denied for members of such communities, in addition to the increased chance of lower house appraisals (McArdle & Acevedo-Garcia);

Adequate childcare still remains to be a luxury to a lot of families around the world, confining women further to their roles as housewives and forcing them to remain in their homes to take care of their children;

Anti-Asian attacks continue to rise after the Covid-19 pandemic, resulting neighbourhoods such as Chinatown’s to be riddled with crime, yet solutions offered involve taking away its affordability, displacing long-established communities in the process;

Cities failing to protect their female inhabitants enough to assure their safety during the night, reducing their chances to see the city during some of its most active moments.

Though they may seem normal to us now, it just comes to show that despite our best efforts, cities still fail, and it’s often because policy-makers exclude and fail to take into consideration the voices that Women of Colour offer during discussions of future city-planning decisions.

Leave a comment